AlphaFold2 for Cyclic Peptide Design - A Deep-dive into Generative Drug Design (2/2)

Cyclic Peptides Generated with AlphaFold

Cyclic Peptides Generated with AlphaFoldThis is Part 2 of my literature review notes on AlphaFold2 for Cyclic Peptide Design. Refer to the 1st part in my blog if you haven’t checked that one out yet!

This 2nd part of my review will be about recreation of the experimental structures of two successful implementations - one by Rettie et. al. and Kosugui et. al. Here are their papers for your reference:

(1) Rettie SA, Campbell KV, Bera AK, Kang A, Kozlov S, De La Cruz J, Adebomi V, Zhou G, DiMaio F, Ovchinnikov S, Bhardwaj G. Cyclic peptide structure prediction and design using AlphaFold. bioRxiv [Preprint]. 2023 Feb 26:2023.02.25.529956. doi: 10.1101/2023.02.25.529956. PMID: 36865323; PMCID: PMC9980166.

(2) Kosugi T, Ohue M. Design of Cyclic Peptides Targeting Protein-Protein Interactions Using AlphaFold. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 Aug 26;24(17):13257. doi: 10.3390/ijms241713257. PMID: 37686057; PMCID: PMC10487914.

Recreation of paper results:

A critical part of the project involves recreating cyclic peptide structures using parameters derived from previous studies. The objective was to validate the implementation of my project, learn the tools required to generate cyclic peptides and reproduce the results to a certain accuracy.

As a high level overview, the recreation process was split into two parts:

(1) 1YCR Complex: Using ColabDesign, 50 structures of cyclic peptides were generated, benchmarked against known metrics. PyRosetta was used for energy scoring.

(2) 12PDB Structures: Cyclic peptides were generated for 11 out of 12 PDBs. Evaluation showed promising candidates, with most predicted structures binding in the expected positions.

Recreation of literature method in 1YCR

Firstly a recreation of the literature method to generate and evaluate generated designs was done with the PDB: 1YCR complex, or the MDM2, p53 peptide complex that is commonly studied. In accordance with the hyperparameters used for Tosugi, T., & Ohue, M, Design of Cyclic Peptides Targeting Protein–Protein Interactions Using AlphaFold, a ColabDesign workflow was developed based on AFDesign Github to generate 50 structures of cyclic peptides of sequence length 13. During the generation, 5 models were used, with standard loss weights, the SGD optimizer, and PSSM_semi_greedy(120,32). Referring to Fig 7, it can be seen that for all seeds, the per residue confidence metric increases greatly in the first 50 iterations, and optimizes as the logits are switched to one_hot_encodings. The median of the generated seeds have a median confidence score (pLDDT) of around 0.73 and a median of around 1.8 i_con value.

Figure 7: 1YCR generation log overview

In the literature, the researchers used a Rosetta program to then minimize the energy score and score the complexes with binding energy normalized by solvent accessible surface area (dG_separated/dSASA *100). In my implementation, I used the PyRosetta API through Google Colab, and used the PyRosetta Interface Analyzer API to generate the energy score. Interestingly, because for each seed an ensemble of 5 models were used during their generation, the output of each generation seed resulted in 5 models in the same PDB. These models vary slightly based on the model weights, and to make use of this, each model output was splitted to generate 5 x 50 = 250 PDB files. The -use_truncated_termini , -run:min_type lbfgs_armijo_nonmonotone, -run:min_tolerance 0.001, -constant_seed -seed_offset 0, Pyrosetta flags were used in the interface analyzer, and the standard energy function REF2015 was used as energy weights. Energy score vs. dSASA and Energy score vs. pLDDT was then plotted as seen in Fig. 8. Upon double checking with the paper, the dSASA scores were aligned with the paper results, however, the energy score was lower than the literature value. This deviation is an area for further exploration in a next-phase of the research. A possible rationale for this would be that the calculation method for the binding energy delta_G may involve some “repacking” parameters to calculate the energy before and after the split.

The same filtering metric was then used as the literature, where compounds with pLDDT >0.7 and a lower binding energy score than the Native were shortlisted, in which 24 out or 50 (48%) PDBs fulfilled this criteria. The RMSD of the 24 candidate PDBs was then selected, with a binding score of -2.734020, dSASA score of 1057.884753, RMSD (no refinement) score of 1.39, and RMSD (w/ refinement): 0.269. As seen in Fig 8, The purple structure (the cyclic design) resembles quite similar and is binding in the same spot as the p53 experimental structure. The only difference is the long tail at the end of the original p53 is no longer presented, but rather replaced by a chain that connects back into the helix structure as seen in purple at Fig. 8, likely caused by the cyclic positional embeddings. PyMOL was used to evaluate the RMSD values through the “Align” plugin that aligns and calculates the RMSD. The percentage of candidates that meet this criteria was less than the literature, but at the same time, only half the amount of structures were hallucinated (50 vs. 100 in the paper).

Figure 8: Recreation of paper results using PyRosetta

Recreation of 12PDB structures in the paper After evaluation from a comparative structure of 1YCB, I further worked to generate cyclic peptides for the 12 PDBs in the paper, 1SSC, 1T4F, 2CNZ, 2V8X, 2Z9I, 3C3O, 3R7G, 3UFM, 3VXW, 4K0U, 4PIQ, 6SEO. Of the 12 PDB target structures, I was able to generate 11 cyclic peptides. For the remaining one, there was an issue with ColabDesign loading in the structure from their mmseqs2 database. The same hyperparameters used in this generation as the generation process for 1YCR. For each PDB, 5 structures were generated, and evaluation was performed with each of the 5 model files in each seed, totalling 25 PDB files.

The same evaluation metric was used as the method performed above with 1YCR to shortlisted candidates. 8 out of the 11 generated models met the sufficient criteria for pLDDT and energy scores. Fig 9. Table provided displays the generated results, suggesting these are potentially good candidates. Whilst for a more optimized output, further iterations could be performed, as only 5 seeds were used in this generation compared to 100 in the paper. The structures of all the 11 generated candidates are then visualized as seen in Fig 9. For the remaining 3 structures, the value with the smallest RMSD was chosen, despite the energy function and pLDDT not fulfilling the criteria. Based on the plots, 9 out of 11 of the predicted structures are in the same relative binding position as the experimental. However, with the remaining two 2V8X and 2Z9I, the cyclic binder position was in a different spot. The case of 2Z9I, the hallucinated compound was found inside of another chain, producing a perhaps infeasible molecule in real life. The reason is because during the generation process, only the specific chain to be targeted was used to generate a compound with. A further exploration will be to either force the AlphaFold model to take in the other chains as a constraint or set specific hotspot hyperparameters to focus the generation on specific regions of the complex. This can improve the control of where the peptide can be generated at.

Fig 9: results of the generated and shortlisted 8 PDB structures

Hyperparameter tuning with HIV gp120 and HPC:

As the next step, I explored into a hyperparameter search in the process of generating HIV gp120 (6X9V) peptides and peptides for the Hepatitis C glycoproteins (7T6X). To explore which hyperparameters influence the results of the generated compound, a hyperparameter search of varying, optimizer and GD_Method was performed. In the first run, the gp120 compound was used to design peptides. Due to the size of the sequence of gp120 (>400 sequence length), each model required 2-3 hours to generate. As a result, due to Google Colab’s 24 hours runtime constraint, the hyperparameter search for all combinations was not complete due to timeout. However, referring to Fig10, the generated results were still sufficient to draw general observations.

First of all, confidence score pLDDT varies greatly with seed generation in the process, this suggests that the initialization of the start peptide sequence greatly determines the confidence later. Analyzing the relationship between the first 4-seeds generated with “pssm_semigreedy” and the yellow portion using “3stage”, it can be seen that use of a PSSM in the 3-stage process optimizes the result. Interestingly, changing the optimizer method will change the final sequence predicted. Across the same seeds, when a different optimizer is used, there are variations in specific regions of the sequence and remain the same for others. The remaining relationship to be determined was how the gradient descent method will impact the predicted confidence of the results.

Fig10: Hyperparameter search of HIV gp120

Another hyperparameter search was then performed with the hepatitis C compound “7T6X”. The rationale to change the molecule was due to more efficient use of computational resources, as the generation time for each 7T6X peptide was much faster (~30 minutes). Three forms of gradient descent were used - the standard Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD), momentum based Adamw, and another adaptive learning method Adagrad. Referring to Fig. 11, it can be seen that for all 4 seeds, the pLDDT and i_con scores are the same across gradient descent methods. This suggests that the gradient descent method converges to the same result. But the fact that changing the seed varies greatly the results suggest that most of these are local minimas that are hard for even momentum based gradient descents to overcome.

Fig11: Hyperparameter search of HPC

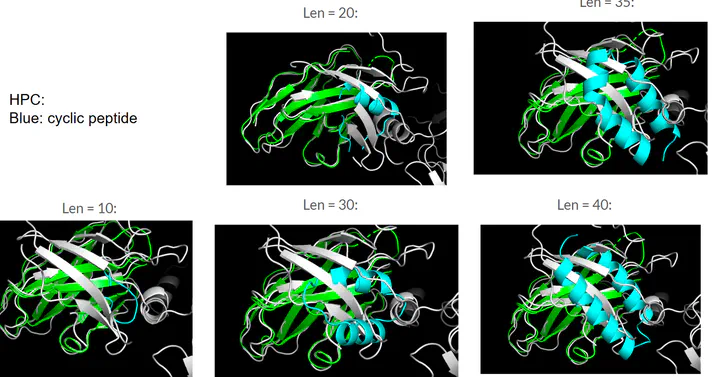

Exploration into how sequence length changes computation length Given the long computational time, another exploration was conducted to understand how increasing the peptide sequence length will increase the peptide generation time. To explore this, 30 models of each peptide sequence of lengths [10,15,20,25,30,35,40] were used to generate cyclic peptides for HPC (7T6X), and the computational time was logged. Fig 11 below shows the relationship chart of the computational time vs. sequence length. Overall there is a general increase in the computational time vs. sequence length. For each sequence, the 1st seed generated takes a longer time, perhaps due to an initial compiling of the model, which later seeds do not need to perform. Changing the sequence length for HPC did not change the position of where the peptide binds to the target, but rather only increases in the number of helices it forms as the sequence length increases. This suggests that changing the sequence length does change the peptide structure, but does not greatly impact the binding area.

Fig 12: Computational time vs sequence length

Generation of gp120 cyclic peptide Lastly, due to the early-runtime stop of gp120 previously encountered, another 5 models were generated of sequence length 13 using SGD, PSSM_semigreedy options for HIV gp120. Based on the generation, there was one candidate that had a confidence score of approximately 0.7, as seen in Fig 12. In purple is the cyclic peptide, which resides in between the gp120 and the adjacent chain. For comparison, highlighted in red is a molecule present in the experimental structure. The cyclic peptide in this case is predicted to bind to a different location than the red molecule.

The Rosetta Interface Analyzer score for this compound was negative, suggesting a potential binding and a SASA of 1195. For further peptide design, the usage of hotspots will be beneficial as it accounts for biological impacts of binding to a certain region over others. The generation of more complexes will also better increase the search space of the binding locations.

Fig 13: Cyclic design for gp120

Areas for further exploration

There are many further areas for exploration into the use of AlphaFold for designing of cyclic peptides. One critical area is reducing the generation time, which currently poses a challenge due to the constraints of the current working set-up. Perhaps the usage of more powerful GPUs could up the process. The ability to generate a large quantity of candidate peptides will provide a more broader searcher space for candidate selection. Secondly, as the backpropagation in the cyclic design process does not account for the biological metrics such as the binding energy & sasa scores. A further exploration will be to integrate key PyRosetta metrics or other biological measurement scores into the peptide generation process, potentially through auto-differential packages such as JAX. This can offer more nuanced control over the optimization process. Additionally, to better control where the peptide is hallucinated against, use of “hotspots” in the gp120 protein—such as particular residue regions—could yield more effective therapeutic candidates. Lastly, in the generation of large quantities of PDBs, another area to explore is the use of clustering methods based on generated torsion angles or other ML methods to refine the selection of promising peptide structures. These explorations hold the potential to significantly advance the field of peptide-based therapeutics for HIV.

Conclusion

Overall, this project was successful in an in-depth exploration into the use of AlphaFold and other bioinformatic tools to generate cyclic peptide strucutres. The project first started with literature reviews to gain an understanding of the AlphaFold architecture and the generation process of new peptides. Based on the understanding, a peptide-generation pipeline was created to recreate results in the literature papers. These structures were then evaluated and shortlisted based on Rosetta scoring metrics to arrive at candidate peptides for each target in the literature. Lastly, an exploration into peptide generation was done with HIV GP120 and Hepatitis-C Glycoproteins to generate cyclic peptide candidates.